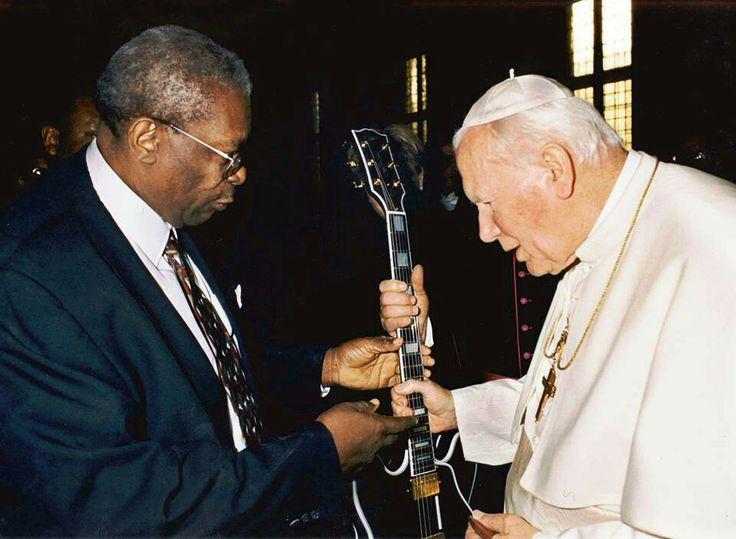

When B.B. King met Pope John Paul II

“Meeting the pope will be a very emotional experience for me, it will be electrifying”

(by mtv news staff 12/19/1997) B.B. King will be presenting his trademark guitar, the legendary “Lucille,” to Pope John Paul II following a performance at the Vatican on Friday, December 19, according to reports by Reuters and the AP.

(by mtv news staff 12/19/1997) B.B. King will be presenting his trademark guitar, the legendary “Lucille,” to Pope John Paul II following a performance at the Vatican on Friday, December 19, according to reports by Reuters and the AP.

Which “Lucille” this is was not noted (the original “Lucille” is long gone, and the blues guitar legend has had a few subsequent axes over the years that have borne the name in turn), but B.B. King’s signature Gibson guitar has been by his side for close to half a century.

“Meeting the pope will be a very emotional experience for me, it will be electrifying,” King told reporters. The performance, at the Pope’s annual Christmas concert, will be taking place at the Paul VI Auditorium, the usual scene of the Pope’s public audiences. King, 72, will have an audience with the Pontiff in advance of the show.

AP reports that the concert is to raise money to build 50 new churches on the outskirts of Rome. King will be joined by fellow American Chaka Khan, the Portuguese group Madredeus and France’s Mireille Mathieu.

The Pope is becoming a regular rock fan. He met folk-rocker Bob Dylan at a concert in September.

Article on B.B. King and his relationship to religion

By Daniel Silliman May 15 at 9:55 AM

B.B. King first learned music from the African American churches of the Mississippi Delta.

“Church was not only a warm spiritual experience,” the legendary bluesman once said, reflecting on his religious childhood. “It was exciting entertainment. It was where I could sit next to a pretty girl and mostly it was where the music got all over my body and made me wanna jump.”

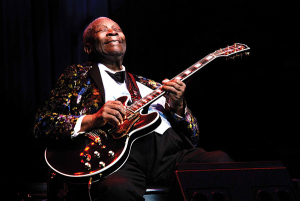

King died on Thursday at age 89. In his long career, he had a profound influence on generations of rock and blues guitarists, as Terence McArdle reported for the Washington Post. King was considered by many to be the world’s best blues singer and came to be known as “King of the Blues.”

[B.B. King, Mississippi-born master of the blues, dies at 89]

In interviews over the years, King talked about how his first experiences with music were connected to church. He also talked about how his relationship to church was deeply conflicted.

The son of sharecroppers in Itta Bena, Miss., King started singing spirituals with his mother at age 4. That was about the time his father left the family. His mother wanted him to grow up to be a preacher, but five years later, she died.

Nine-year-old King kept singing.

He was attracted to the Church of God in Christ because of the music. The King family had been Baptist. The Baptists’ musical tastes were more staid, more traditional than the young King liked, however.

“If you were in the Baptist church, they didn’t want you to bring a guitar in,” he said in an interview with the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1999. “So I didn’t really dig the Baptist church too much.”

The pastor of the local Church of God in Christ, on the other hand, played a Sears Roebuck Silvertone guitar. The Rev. Archie Fair led church with his guitar.

The church was a part of a strict sect of pentecostals, who believed true Christians could live free from sin, “sanctified.” In some ways, the Church of God in Christ was more conservative than the Baptists. But not when it came to music. King thrilled to the church’s worship style.

One fateful Sunday, a pentecostal pastor taught King to play three basic chords.

After that, King was converted.

He volunteered to be a janitor at the church so he could spend time with the instruments. Though King worked all week in the cotton fields, he taught Sunday school to children younger than himself. He got the nickname “church boy” and didn’t care.

King soon found more thrilling music outside the walls of church, though. An aunt, only a few years older than King, exposed him to her collection of 78 rpm records. She played him Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson. He started going to the store in Indianola, Miss., on Saturdays to listen to the blues on the radio. A cousin, Booker “Bukka” White, was living in Memphis, making a living playing the blues, and would come back to Mississippi sometimes with a beautiful guitar and sharp new clothes.

Still, the blues seemed shameful to King. They were exciting but felt wrong.

“I was ashamed, man,” King told the BBC in 1972. “The people around us was very religious. I always say they were very religious, very hypocritical. Because, if they wasn’t religious, they seemed to act the part.”

Some of those religious people liked the same music that King did but kept it secret. As he recalled in a 1980 interview with music journalists Tom Wheeler and Jas Obrecht, “they would play their blues after midnight, when they were in their room and nobody could hear them.”

The young King thought he liked the blues because of the devil inside him.

Journalist Joseph Nazel, in his biography of King, writes that “the blues, once the music became popular enough for the press to take note, became a cause of conflict and contention among those, both black and white, who saw the blues as ‘devil music’ which would somehow corrupt them all.” White opposition was racial. They saw the music as primitive, “jungle music.” Black opposition was based in respectability politics. The music was an embarrassment because it was associated with drinking and dancing.

“They did not care,” Nazel writes, “that the blues was based on the same expressive rhythms as more religious music.”

As a teenager, King stuck to the religious versions of those rhythms. His first group was called the Elkhorn Jubilee Singers. Later he played with the Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers.

The Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers weren’t actually famous but did achieve some popularity in black churches across the Delta region. The group even performed several songs live on the radio, at stations in Greenwood and Greenville, Miss. The Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers ran into trouble, though, because of King’s guitar. He pushed, musically, bringing the blues into church. It upset the more staid Christians. The group got a reputation for being rebellious and a little too inappropriate for church. Some of their invitations were rescinded.

King, at the same time, was growing frustrated with religious audiences for his own reasons. When he played for church people, they would say “God bless you,” but wouldn’t give him any money. He noticed non-religious audiences were different while playing on the corner of Church and Second Street in Indianola, at the intersection of the black and white parts of town.

“People that would request a gospel song would always be very polite to me,” King recalled in 1999. “And they’d say, ‘Son, you’re mighty good. Keep it up. You’re going to be great one day.’ But they never put anything in the hat.”

When he played the blues, though, people would give him a little money or beer. On at least one occasion King recalled singing a spiritual song, changing the word “my Lord” to “my baby,” and getting a tip and a free beer.

“Now you know why I’m a blues singer,” King said.

When he was drafted into the Army in 1943, King stopped playing religious music. When he got out, he moved to Memphis and started playing in taverns and juke joints. He got his first hit in 1951 with “3 O’Clock Blues,” recorded in a makeshift studio in the back of the Memphis YMCA. It was a song about a man missing a woman in the middle of the night.

He was done with church music. He was even done with Christianity.

In a 2006 interview with British journalist Elaine Lipworth, King said that Christianity and the blues were opposed forces in African American history.

“A lot of the slave masters were teaching Christianity to the blacks because they thought if they were Christians they wouldn’t steal or wouldn’t run away. But some of them were going to be sold anyway, so they didn’t care and would play and sing about things that made them happy and made them feel good,” he said. “I guess I’m a disciple of some of those slaves.”

Still, like Nazel and many other music historians, King recognized how deeply these musical styles were related. The secular and the sacred were not always obviously distinct. Even on his hit single, it was possible to replace “my baby” with “my Lord” and make the blues song into a spiritual.

“Goodbye everybody,” King sang. “Lord, I believe this is the end. / Well tell my pretty baby to forgive me for my sin.”

This was something King acknowledged.

“There’s a blues for anything that bothers you,” he said. “I listen to gospel music and, believe it or not, I hear the same thing. The only difference is these people are praying to God or Jesus. The bluesman would be saying, ‘Open the door. Don’t keep me waiting. The gas station is closed. Let me in’ — that kind of thing.”

Despite that recognition, King didn’t find his way back to church in his later years. He remembered the Church of God in Christ fondly, and said in interviews that “the sanctified people are the singingest people.” He also remembered the Rev. Archie Fair fondly, and when he performed for Pope John Paul II in 1997, King said the pope reminded him of the Mississippi pentecostal preacher of his youth. Both men, he said, made you feel like they could get a message to God on your behalf.

Even then, King was conflicted, religiously.

“I don’t know what happens after this life,” he said. “I haven’t had my mother or anybody else come back and tell me. I think hell is hell on earth. And heaven to me is a beautiful lady and enjoyment with her.”